When we look up at the Moon, it’s easy to imagine it as a static, airless rock. But beneath that ancient surface lies a dynamic and revealing history—one shaped by seething magma oceans, metallic cores, and perhaps even hidden reservoirs of water.

Understanding the Moon’s interior isn’t just about deciphering lunar geology; it’s about unlocking clues to how planets form, evolve, and become habitable. And much of my research has focused on using modeling, geophysical data, and mission-derived constraints to peel back those layers—literally.

A Fiery Beginning: The Lunar Magma Ocean

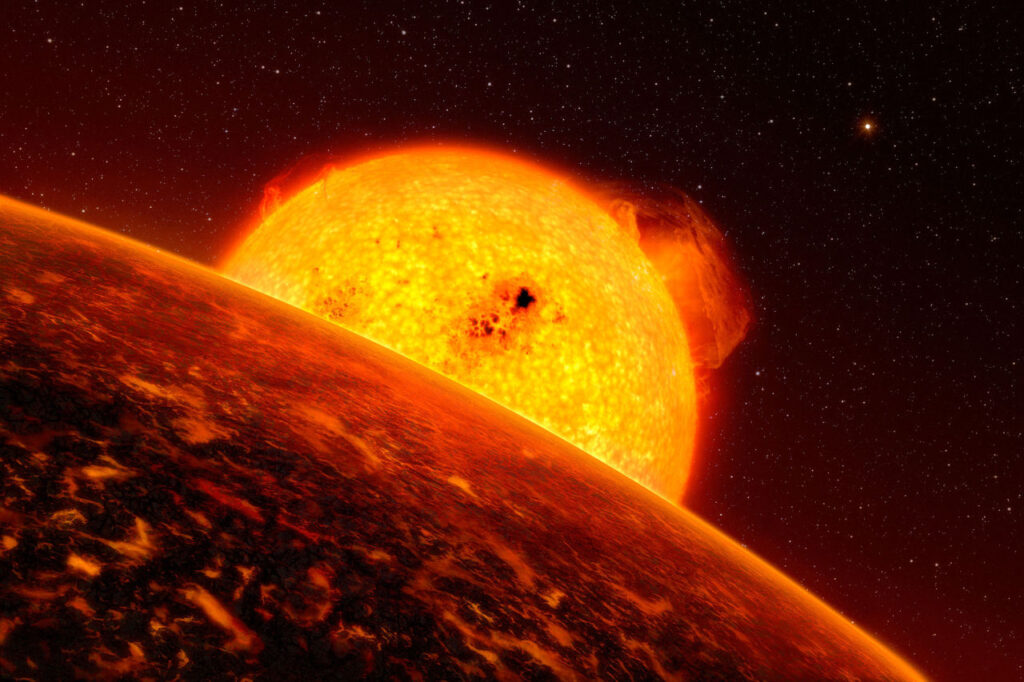

Shortly after the Moon formed—likely from a giant impact between a Mars-sized body and early Earth—it was completely molten. This global “magma ocean” began to crystallize from the bottom up, with denser minerals sinking and lighter ones floating to the surface.

That solidification process created a layered internal structure: a crust rich in plagioclase, a mantle with denser silicates, and a possible metallic core. But it also left behind important geochemical and thermal fingerprints.

My work uses thermochemical modeling to simulate how this magma ocean evolved, how long it stayed molten, and how heat transfer affected early tectonics. We’ve found that the rate of solidification, presence of residual melt, and early overturn events had profound effects on crust formation and volcanic history. These aren’t just academic models—they help explain why we see regional crustal differences and why certain parts of the Moon are more volcanically active (read more).

Seismic Clues and Interior Structure

Thanks to Apollo-era seismometers—and more recently, data from missions like GRAIL and LRO—we have constraints on crustal thickness, mantle layering, and potential core size. By integrating gravity and topography data with thermal evolution models, we’ve shown that the Moon’s mantle may still retain zones of partial melt, especially beneath large impact basins.

These partially molten regions could have fed the Moon’s prolonged volcanic activity—activity that continued well into the last billion years, longer than previously thought. Such findings challenge our assumptions about what a “dead” body like the Moon can do and suggest we may need to revisit models of heat retention and mantle dynamics.

Water on the Moon: A Paradigm Shift

For decades, we believed the Moon was bone dry. But that belief has changed dramatically. Data from missions like Chandrayaan-1, LCROSS, and analyses of Apollo samples with modern instruments have revealed traces of water in lunar volcanic glass, minerals, and permanently shadowed regions.

My work builds on this by connecting volatile retention and migration to the Moon’s thermal and chemical history. We ask: How did water survive the Moon’s violent formation? Where is it stored today? And how might it be extracted or used by future human missions?

Answering these questions isn’t just about exploration—it’s about planetary evolution. If the Moon, formed in such a high-temperature environment, still has water, what does that mean for other rocky worlds? And how might volatiles be redistributed during planetary formation?

Why It Matters

Understanding the Moon’s interior has practical implications. It informs where we send landers, how we build habitats, and what we look for in terms of resource extraction. But more broadly, it tells us about the life cycle of terrestrial bodies, and how heat, water, and time shape the environments we see today.

At LunaSCOPE, we’ve integrated seismic, thermal, and magnetic data to build a cohesive, 3D model of the Moon’s interior evolution. This model doesn’t just satisfy scientific curiosity—it supports mission planning, surface operations, and our long-term presence on the Moon.

Further Reading & Resources:

NASA LRO – Lunar Interior Science

GRAIL Mission Findings on Crustal Structure

Lunar Water Discovery via Volcanic Glass (Saal et al., 2008)

Image Credit: Artist’s impression of exoplanet CoRoT-7b / ESO/L. Calçada